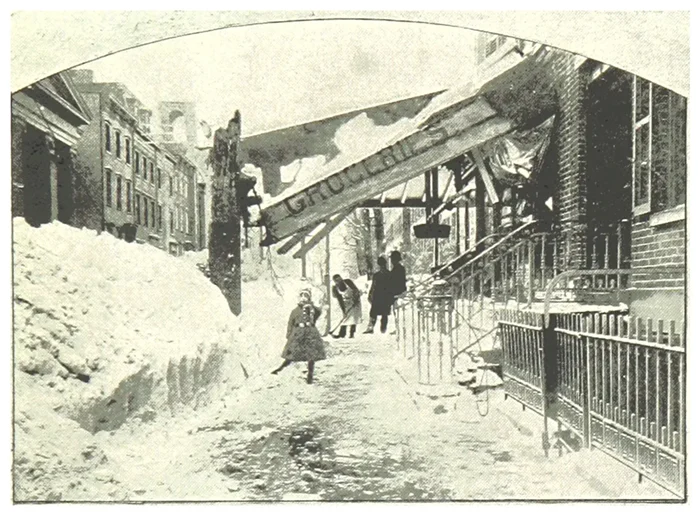

From March 11 to 14, the entire Northeast was battered by relentless snow, hurricane-force winds, and bitter cold that turned one of America’s most advanced cities into a frozen labyrinth.

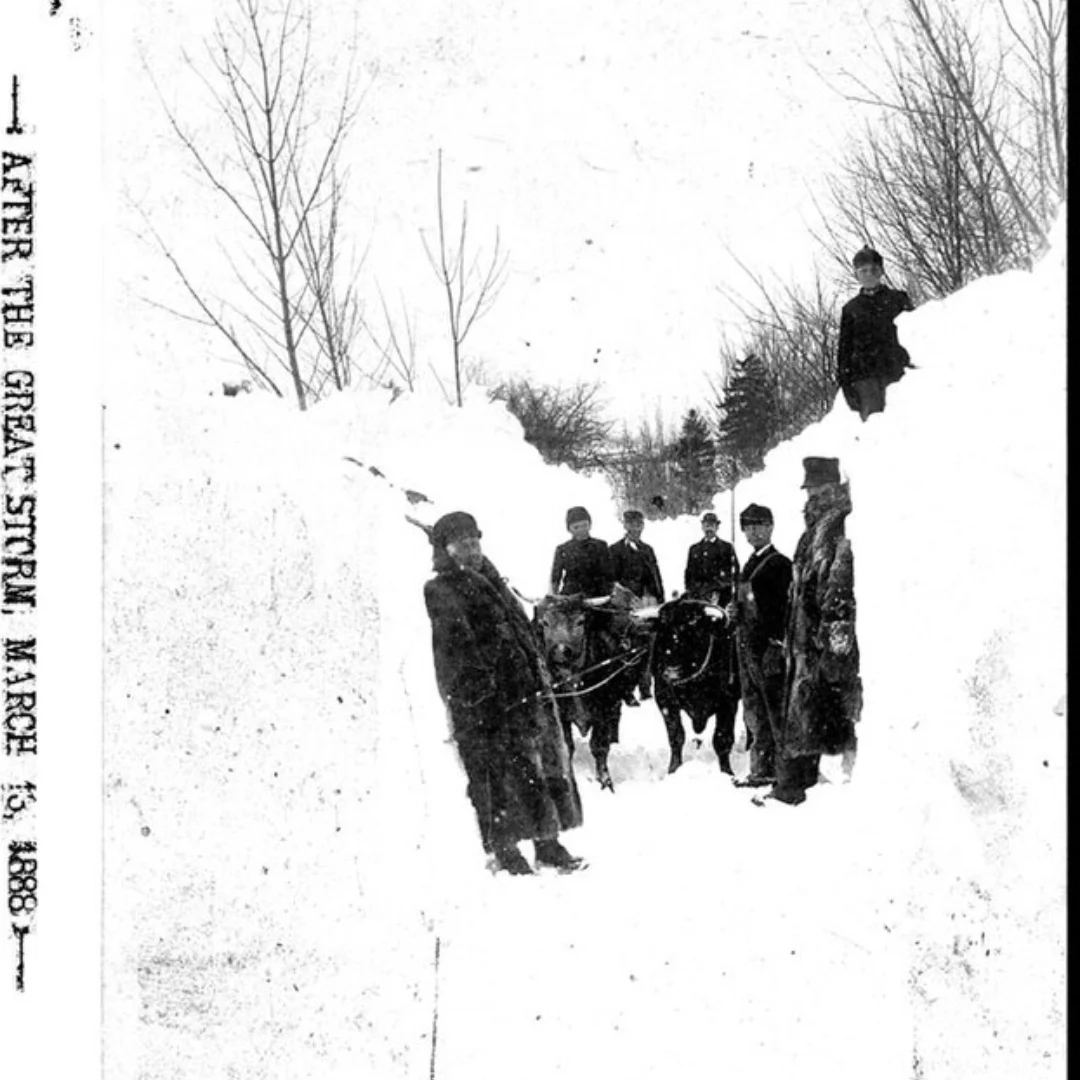

Snow began to fall on March 11 and didn’t stop for nearly four days. By the time it ended, parts of New York were buried under as much as 40 inches of snow, with wind gusts exceeding 45 mph creating drifts over 20 feet high and in some places, even taller. Brooklyn recorded a drift of 52 feet, the highest ever reported.

A Storm Like No Other

Entire streets disappeared. Doors were blocked, windows were buried, and some residents were forced to dig tunnels from their front doors just to reach the nearest cleared path. Elevated train lines froze in place, leaving thousands of commuters stranded in the city or unable to return home.

“Before the day had well advanced, every horse-car and elevated railroad train in the city had stopped running; the streets were almost impassable to men or horses by reason of the huge masses of drifting snow; the electric wires — telegraph and telephone — connecting spots in the city or opening communication with places outside were nearly all broken…”

—The New York Times*, March 13, 1888 (“In a Blizzard’s Grasp”)

A Catalyst for Change

The paralyzing storm didn’t just disrupt daily life; it exposed the vulnerabilities of a modernizing metropolis. The shutdown of elevated trains and the citywide chaos directly influenced one of New York’s greatest infrastructural advancements: the creation of the underground subway system. In fact, Boston’s subway, the first in the United States, was developed soon after, inspired by the gridlock New York had faced.

But the blizzard’s impact didn’t stop there. Telegraph and telephone lines snapped under the weight of ice, cutting off communication up and down the East Coast. With supplies dwindling and rescue efforts hampered, the storm revealed just how fragile the region’s above-ground systems were.

In response, city planners and engineers began moving vital infrastructure underground, from telegraph cables to transportation networks, changes that would define New York’s future resilience. The Blizzard of 1888 taught New York a lesson it never forgot: that progress meant moving underground.

A Turning Point in Weather Forecasting

In 1888, meteorology was still in its infancy. Without satellite imagery, radar, or reliable forecasting, the blizzard arrived as a complete surprise. The disaster spurred the U.S. Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) to expand and modernize its forecasting and communication systems, laying the groundwork for the predictive tools we rely on today.

The Blizzard’s Enduring Legacy

The Great Blizzard of 1888 remains one of the most extreme winter storms in American history, not just for its physical destruction but for how it reshaped urban planning and public safety. It stands as a powerful reminder that extreme weather doesn’t just change the landscape, it changes society.

From that frozen March in 1888 came a new vision of a city better prepared for the future, built not just to survive the elements but to adapt because of them.

Sources: National Weather Service / Wikipedia, nysubway.org

Image: “Blizzard of March 1888 – Deep cut in ‘Hardscrabble’ Road,” by J.A. French, Keene, NH

Featured Image: “The Blizzard of March 1888,” by Langill